21 Aug Criminal Responsibility: Psychological Evaluations & Case Study of the Moore, OK Beheading

Abstract

When an individual commits a crime, there may be several evaluations which are ordered by the court. One of the most important will often be that of criminal responsibility. This speaks to the defendant’s state of mind during the criminal act for which he is to stand trial. There are many reasons a defendant may be found ‘not guilty for reason of insanity.’ However, experts for opposing counsel often disagree on their findings; even when the tools used to conduct the evaluations are similar and in spite of the fact that their training and code of ethics are very similar if not the same. The purpose of the paper is to review existing empirical data and literature on the processes and instruments used in the psychological evaluations which determine criminal responsibility in court cases. The paper will also review data which supports said evaluations and instruments as well as any which may refute their validity. Using existing case law as well as conducting a case study of a recent capital murder case, this author will scrutinize contradicting expert testimony to go beyond why and when these evaluations are conducted but also look to review their validity.

Keywords: criminal responsibility, forensic psychology, Alton Nolan, expert witness, M’Naghten

Introduction

The mental state of a defendant at the time of the offense (MSO) is used to determine criminal responsibility. The most frequently invoked defense as it relates to MSO is insanity. It is believed that some individuals are so mentally ill that they are unable to control their criminal behavior or so irrational in the thought process which drives said behavior that to apply typical punishment would be cruel and unusual. It is important to differentiate criminal responsibility from that of competence. Criminal responsibility is dependent on the mental state of an individual at the time the crime took place; whereas competency examines an individual’s mental state during the trial. However, evaluations are required for both (Melton, Petrila, Poythress, & Slobogin, 2007).

Not all states recognize or allow the insanity defense. For example, Kansas, Utah, Montana, and Idaho do not allow for the insanity defense, but Idaho, Montana, and Utah do allow ‘guilty but insane’ verdicts. Those who do the defense, require an evaluation to be conducted by an expert in order to recreate the thought process as it relates to the defendant’s behavior before and during the alleged crime. It is not unusual for defense counsel, as well as the prosecution, to secure their own expert(s) (Melton et al., 2007). On rare occasions, the court may also secure an expert for an evaluation (Oklahoma v. Nolan, 2017).

Legal Issues

There are several standards on which the insanity defense has been based. Perhaps the earliest and most recognized is M’Naghten. Also known as the M’Naughten Standard (Ferguson & Ogloff, 2011), it requires findings that the individual’s mental state rendered them incapable of knowing what they were doing or that their behavior was wrong. This standard faced early criticism because it did not include an individual’s ability to control their behavior and because it was thought to be too rigid in its requirements (Melton et al., 2007). Ferguson and Ogloff (2011) further contended the verbiage used by M’Naghten was not as clear as it appeared (Melton et al., 2007).

In response to these criticisms, the Durham Rule was adopted. The rule asked two questions: (1) Was the mental disease present at the time the crime was committed, and (2) Was the criminal act the product of the mental illness? The Durham Rule was eventually dismissed because it did not provide a definition of either ‘mental disease’ or ‘product.’ Nor did it specify the extent to which the mental disease had to influence the behavior; in other words, mens rea or relevance of the mental disease was not addressed under Durham. Today, most states use the M’Naghten Rule as it was originally adopted or a modified version which may include the American Law Institute’s (ALI) test or the ‘impulse test’ (Melton et al., 2007).

Influencing Factors

Despite the courts’ insistence of offering the insanity defense only to those who have a diagnosable mental illness, there are some who argue that economic and environmental factors have proven psychological impacts; and thus, should be considerations in the allowance of such defense (Melton et al., 2007). One such example was Shuman and Gold’s (2008) take on impulse aggression. Using State v. Balderama and State v. Christensen, the authors argued that if mental illness was relevant to criminal responsibility, then expert witnesses should be permitted to speak to a defendant’s ‘impulsivity’ or ‘abnormal mental state’ during the crime. However, under M’Naghten impulsive aggression is not permitted as evidence in most of the states which adhere to the rule. The authors contend that more research should be conducted in this area because what little exists has demonstrated impulse aggression could be a factor in the determination of criminal responsibility

Carroll, McSherry, Wood, and Yannoulidis (2008) discussed the issues related to drug-induced psychosis and how it related to criminal responsibility. Specifically, they addressed the issue with drawing a distinction between allowing the insanity defense when psychosis is internally triggered and refusing to permit the same defense when the psychosis is externally triggered after exposure to illicit drugs. Using the terms such as ‘drug-associated psychoses’ and ‘intoxication syndrome,’ the authors used empirical data from studies on the occurrence of psychoses during exposure to cannabis (D’Souza et al., 2004b; D’Souza, Cho, Perry, & Krystal, 2004a; Tramer et al., 2001; Verdoux, Gindre, Sorbara, Tournier, & Swendsen, 2003) and amphetamines (Wilson, Kalasinsky, & Levey, 1996), to suggest the consideration of allowance. Further contending the links demonstrated in these studies between illicit drug use and violence were too great to ignore. (Carroll, et al., 2008).

According to Melton et al. (2007) drugs (Iowa v. Hall, 1974) as well as alcohol may be a consideration in an insanity defense; but contended its success was dependent “on whether intoxication [was] voluntary, involuntary or the result of a long-term addiction or use” (p. 229). However, allowance has not often equated to its success as an insanity defense. In some states, the introduction of such evidence is not even permitted.

In Montana v. Engelhoff (1996) state statute denied the introduction of such evidence. Engelhoff was charged with killing two people. He claimed his intoxicated state was involuntary and rendered him physically incapable. The court refused to allow involuntary intoxication evidence to be heard by the jury and he was convicted. He appealed on the grounds that the state violated his due process and the Montana Supreme Court reversed the decision. However, the US Supreme court ruled that Montana’s statute which prohibited involuntary intoxication evidence for the defense was not a violation of the defendant’s due process. The precedence set by this case has allowed states to prohibit such evidence.

Other influencing factors which have been discussed are Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Friel, White, & Hull, 2008), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Grant, Furlano, Hall, & Kelley, 2018); genetics (Melton et al., 2007; see also Morse, 2011); epilepsy, dissociative states, and impulsive disorders (Melton et al., 2007). Disorders such as Hypoglycemic Syndrome (Twinkie defense) (Melton et al., 2007), and Frontal Lobe Syndrome (FLS) (Sener, Ozcan, Sahingoz, & Ogul, 2014), may also be influencing factors because they can mimic symptoms similar to that created by some mental illnesses. Specifically regarding FLS; Sener et al. (2014) recommended that clinicians examine medical history prior to the criminal act for indicators and when FLS is present, it should be a consideration in the assessment of criminal responsibility.

The practice of Forensic Psychology in the Courtroom

According to Ferguson and Ogloff (2011), psychologists (experts) are responsible for the evaluation of a defendant in order to determine the presence of mental illness at the time of the crime and during the trial, as well as the extent to which it may have impacted the behavior of the defendant or likelihood it may result in the future. For the purpose of this paper, the only evaluation which will be addressed is that which is related to MSO.

Psychologists are bound in practice by a code of ethics set forth by the American Psychological Association (APA). Those who work specifically in forensic psychology are provided specific guidelines by which to operate by the American Psychology-Law Association (APLS) and the National Organization of Forensic Social Work (NOFSW). These codes provide a standard for ethical practice to preserve the integrity of the profession. They are meant to be aspirational and not mandatory. However, experts who are found to be operating outside of these guidelines may damage their reputations to a point where they are no longer able to work in their chosen profession (Melton et al., 2007).

According to Melton et al. (2007), a variety of instruments may be used to assist experts in criminal responsibility evaluations. These help experts determine the existence of mental disease and the extent to which it may have influenced an individual’s behavior during the crime. One such instrument is the Rogers Criminal Responsibility Assessment Scale (RCRAS). This test consists of 25 scales which are intended to measure variables which may impact an individual’s mental status. These include possible malingering (faking symptoms), potential spontaneous conditions, low IQ, functional disturbances, language or thought barriers, and hallucinations. Other tests frequently utilized are the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI/ MMPI-2), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), Rorschach Inkblot Technique, Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WISC-IV). Though Ferguson and Ogloff (2011) contended MMPI and Rorschach to be among the least reliable due to the fact that they “have both fared poorly at distinguishing between groups of offenders found guilty, and those found not criminally responsible” (p.87). The authors agree RCRAS is useful and add the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) to Melton’s list of instruments. Laboratory tests which have been suggested but not necessarily used on a regular basis have been Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT). These have been seen to have a positive effect on juries; though usually in favor of the defense (Melton et al., 2007).

Another widely used test is the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R). The test is more commonly used in clinical settings and “is a 90-item self-report instrument designed to assess mental health symptoms across nine subscales generally associated with mental health pathology” (Grande, Newmeyer, Underwood, & Williams, 2014, p. 271). The subscales include obsessive-compulsive, depression, hostility, paranoid ideation, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism. Individuals are asked to rate their symptoms in severity on a scale of zero to four (zero being none and four being severe). However, this instrument has been challenged in its diagnostic ability and general utility (Grande et al., 2014).

Melton et al. (2007) pointed out that despite the success or perceived successes, these instruments should be used sparingly in criminal responsibility because they measure the current functionality of an individual and attempt to apply that to the MSO. Information derived from these instruments is often marginally relevant because the nature of the disorders has been to change or even spontaneous remission. The instruments test functionality on a general level whereas behaviors relating to MSO is very specific. Finally, sound empirical studies and literature regarding links between “diagnostic conditions and legally relevant behavior” are almost unheard of (Melton et al., 2007, p. 257).

Despite an expert’s training, available instruments, guiding law, and ethical codes, some believe it is not possible to retrospectively evaluate an individual’s MSO. This is especially true considering that many evaluations are conducted a significant period of time after the crime was committed (Ferguson & Ogloff, 2011). Often experts use the same instruments to conduct evaluations on an individual and their finding can be completely different. The following is a case study that demonstrates this point.

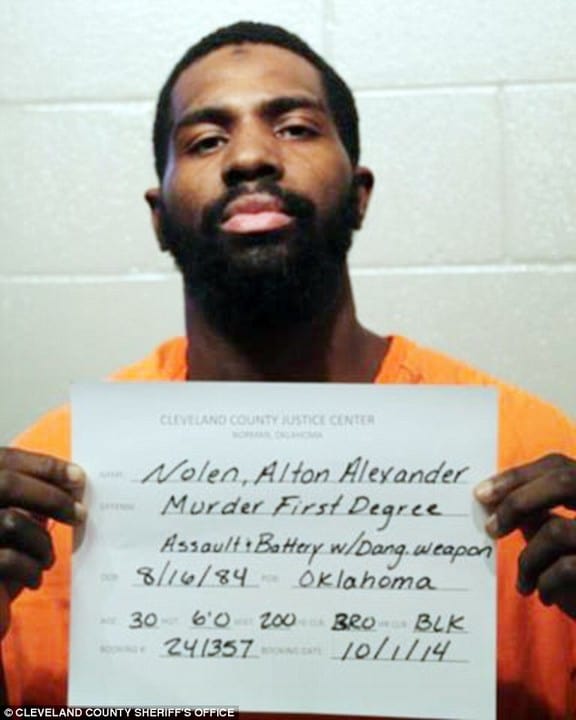

Case Study: Oklahoma v. Nolen

On September 25, 2014, Alton Nolen was suspended by his employer (Vaughn Foods) for complaints made against him. It had been reported that the recent convert to Islam had been hostile towards his coworkers and made racist comments when they resisted his efforts to convert to his religion. The human resource department had Mr. Nolen relinquish his access badge, and he was escorted from the building. Mr. Nolen drove home, where he retrieved a knife, put it in his boot, and then returned to Vaughn Foods. Conflicting reports indicate he waited in the parking lot for shift change while others say he crashed his vehicle into another parked car and then entered as other employees were exiting. Once inside the facility, Mr. Nolen grabbed Collen Hufford from behind and began using the knife to slash her throat. Colleen fought back as evidenced by the wounds on her hands and arms. Her coworkers also attempted to stop the attack. They were unsuccessful, and Mr. Nolen killed and ultimately beheaded Colleen. Mr. Nolen was then successful in seizing Tracy Johnson and began to attack her in the same manner (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

During the initial attack, the Chief Operating Officer, Mark Vaughn (and reserve deputy for Oklahoma County) ran to his vehicle where he retrieved his vest and rife and then ran back inside to confront Mr. Nolen. When Mark arrived, he pointed his weapon at Mr. Nolen, drawing his attention from Tracy. Mr. Nolen released Tracy and charged Mark. Mark shot Mr. Nolen, wounding him. Mr. Nolen was taken to the hospital where he was treated and placed into custody (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

During his initial evaluations, which were sealed by the courts but referenced in part in later testimony, Mr. Nolen requested to plead guilty and to receive the death penalty. Because of this request, his attorney ordered several evaluations and against the wishes of his client, entered a plea of ‘not guilty by reason of insanity.’ During the trial, several expert witnesses testified on behalf of the defense, the State, and the court. Mr. Nolen was ultimately found guilty and sentenced to death in December of 2017. The jury found him guilty despite the testimony of two expert witnesses who claimed he was not criminally responsible because he was insane at the time of the act and perhaps a few times during the trial (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Defense Expert

Dr. Ann McGarrahan presented as a forensic psychologist and neuropsychologist. She was hired by the defense after their first expert failed to find Mr. Nolen mentally ill to an extent that would meet the state statutory criteria for a defense (this first witness would later recant her diagnosis and claim the defendant was sufficiently mentally ill). Prior to the evaluation, Dr. McGarrahan reviewed the defendant’s school records, some personal records, records from the Department of Corrections, multiple mental health evaluations (raw test data from other psychologists), psychiatric records from the Oklahoma Forensic Center, some medical records, and court transcripts from prior hearings. She also conducted collateral interviews with three of Mr. Nolen’s family members (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Her evaluation of the defendant took place over a two-day period and totaled nine hours. She noted Mr. Nolen was not always cooperative and often responded ‘no comment.’ At times he refused to look at her and made remarks that her feet and other parts of her body should not be displayed to him. She described such behaviors as paranoia. Dr. McGarrahan sought the council of Dr. Robert Hunt to get clarification on the Muslim faith. She contended it was important to not classify cultural norms as mental illness. Based on Dr. Hunt’s report, she did not believe the defendant’s claims to Islam represented a norm. She did, however, describe his propensity to steer all conversation back to his religion as ‘hyperreligiosity’ (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Although there were several references to ‘tests’ throughout Dr. McGarrahan’s testimony, the exact tests administered were not discussed. There are references to an IQ test and possible low scores, but these references were objected to by the prosecution as they were not to be discussed in phase one of the trial (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Dr. McGarrahan argued that the defendant’s insistence on pleading guilty was irrational because he knew he was facing the death penalty if found guilty. She believed his motivation to cooperate with her evaluation was high but only in that he wanted to prove he was not insane. She described Mr. Nolen as highly distractible, lost easily in thought, and may have been suffering from hallucinations. Interviews with his family members revealed a family history of mental illness (though this was not collaborated by any records). Dr. McGarrahan diagnosed the defendant as having schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Court Expert

Dr. Shawn Roberson was secured as a witness when the court ordered the Department of Mental Health to conduct an evaluation of the defendant prior to trial. He presented as a psychologist trained in forensic evaluations, having performed over 3,000 in his career. At the time of trial, he had a private practice. Prior to the evaluation, Dr. Roberson reviewed all documents relating to the current charges against the defendant and prior criminal records. He conducted research to determine if Mr. Nolen had been previously hospitalized at any facility within the Department of Mental Health or other treatment facilities in the area. He also inquired at the detention center as to the defendant’s behavior, issues, or medications. Dr. Roberson then conducted a one-hour structured interview with Mr. Nolen (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Dr. Roberson administered the SCL-90-R test to the defendant. He indicated Mr. Nolen appeared to take his time, carefully considering each of the 90 questions. Dr. Roberson did acknowledge SCL-90-R was not his first instrument of choice. He preferred the MMPI but believed the defendant would not have completed a test which was comprised of some 500 questions (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

Dr. Roberson indicated the defendant was cooperative but at times did not address the questions as they were asked; choosing instead to discuss his religion. He stated Mr. Nolen sought to portray himself as a very religious and pious man. In reference to him not wanting to see Dr. McGarrahan’s feet, Dr. Roberson contended the defendant was a particularly controlling individual but not paranoid. Additionally, he did not find Mr. Nolen to have hyperreligiosity but reported him to be narcissistic (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

When Dr. Roberson questioned the defendant about his behavior, and if he understood it to be wrong, he responded that Allah would judge him. Mr. Nolen further explained that it was a sin for a Muslim to lie and to allow his attorney to plead the insanity defense for him was akin to lying. The defendant further claimed only the law given to the prophets should be used to judge him. Dr. Roberson concluded that although the defendant was a hostile individual, he did not suffer from mental illness at the time of the trial or the crime. He believed he understood his actions were wrong and knew the consequences (Oklahoma v. Nolen, 2017).

The defendant’s counsel has since appealed the verdict, and a stay of execution was issued in January 2018. The appeal is currently being reviewed (J. Johnson, personal communication, June 27, 2018). No doubt testimony from all expert witnesses, as well as the test results and evaluation reports, will be a consideration in any future outcome of this case. It is important to note that at the time this paper was written, not all testimonies from this case had been transcribed. The author was limited to testimony from the aforementioned experts.

Limitations & Opportunities for Future Research

Despite the reliance judges and juries place on criminal responsibility evaluations (Melton et al., 2007), not everyone in the criminal justice system believes such evaluations are valid. There have been several studies that dispute the instruments used (Ferguson & Ogloff, 2011; see also Melton et al., 2007; and Grande et al., 2014) and the validity of the evaluations themselves (Melton et al., 2007).

Perlin (1989) contended despite “centuries of jurisprudential evolution, the insanity defense doctrine remains incoherent” (p. 601). The author felt “the post-Hinckley substantive and procedural shrinkage of the insanity defense may be viewed as an inevitable consequence of societal fear of and ambivalence toward dynamic psychiatry” (p. 603). However, it is important to note that The Insanity Defense Reform Act (post-Hinckley) only applies to federal court. He further contended the evolution of the defense (M’Naghten through ALI) was irrational.

Urbaniok, Laubacher, Hardegger, Endrass, and Moskvitin (2012) believed the validity of MSO evaluations should be questioned for other reasons as well. They contend research has failed to take free will into consideration regarding criminal responsibility. The authors analytically scrutinized the three fundamental concepts on which neurobiological determinism was constructed:

(1) Causality – All human behavior is caused by unconscious biological processes [neurobiological processes] in the brain…: (2) Determinism – …Because all human behavior is caused by unconscious neurobiological processes, there is no possibility to behave in a different way…: (3) Lack of human accountability and criminal responsibility – Because all human behavior is completely determined, there can be no individual guilt for a crime (Urbaniok et al., 2012, p. 176).

Human behavior could not entirely be attributed to such factors and there are no current medical findings which suggest the principle of guilt should be questioned. The rationale behind neurobiological determinism was attributed to defective experimentation and methodical misinterpretation (Urbaniok et al., 2012).

Conclusion

Psychologists utilize their training, ethical codes, and instruments to assist in determining the mental status of a defendant at the time a crime was committed. There are many factors which may impact said mental status. Juries and judges rely heavily on such evaluations. However, expert witnesses for opposing counsel often come to different conclusions. Literature and empirical studies demonstrate equally conflicting information regarding the validity of both the instruments used and criminal responsibility evaluations as a whole.

Cases such as Oklahoma v. Nolen demonstrate the complexities of the insanity defense, in particular when the defense is against the wishes of the defendant. Such cases should be utilized in future research considerations. In addition, the instruments used and possible contributing factors warrant further empirical studies. The propensity to overlook freewill in lieu of neurobiological determinism represents gross oversight at best and negligence at worst. Much like intent, criminal responsibility may just be subjective.

References

Carroll, A., McSherry, B., Wood, D., & Yannoulidis, S. (2008). Drug-associated psychoses and criminal responsibility. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 26, 633-653. doi: 10.1002/bsl.817

D’Souza, D. C., Cho, H., Perry, E. B., & Krystal, J. H. (2004a). Cannabinoid ’model’ psychosis,

dopamine–cannabinoid interactions and implications for schizophrenia. In D. Castle, & R. Murray (Eds.), Marijuana and madness (pp. 142–165). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Souza, D. C., Perry, E., MacDougall, L., Ammerman, Y., Cooper, T., Wu, Y., Braley, G.,

Gueorguieva, R., & Krystal, J. H. (2004b). The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: Implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29, 1558–1572. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp. 1300496.

Ferguson, M., & Ogloff, J. R. (2011). Criminal responsibility evaluations: Role of psychologists in assessment. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 18 (1), 79-94. doi: 10.1080/13218719.2010.482952

Friel, A., White, T., & Hull, A. (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorder and criminal responsibility. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 19 (1), 64-85. doi: 10.1080/14789940701594736

Grande, T. L., Newmeyer, M. D., Underwood, L. A., & Williams, C. R. (2014). Path analysis of the SCL-90-R: Exploring use in outpatient assessments. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 47 (4), 271-290.

Grant, T., Furlano, R., Hall, L., & Kelley, E. (2018). Criminal responsibility in autism spectrum disorder: A critical review examining empathy and moral reasoning. Canadian Psychology, 59 (1), 65-75. doi: 10.1037/cap0000124

Iowa v. Hall, 214 N.W. 2d 205 (1974).

Melton, G. B., Petrila, J., Poythress, N. G., & Slobogin, C. (2007). Psychosocial evaluations for the courts, Third Ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Montana v. Engelhoff, 116 S.Ct. 2013 (1996).

Morse, S. J. (2011). Genetics and criminal responsibility. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15 (9), 378-380.

Oklahoma v. Nolen, 36 P.2d 954 (2017).

Perlin, M. L. (1989). Unpacking the myths: The symbolism mythology of insanity defense jurisprudence. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 40 (3), 599-731.

Sener, M. T., Ozcan, H., Sahingoz, S., & Ogul, H. (2014). Criminal responsibility of the Frontal Lobe Syndrome. Eurasian Journal of Medicine, 47, 218-222. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2015.69

Shuman, D. W., & Gold, L. H. (2008). Without thinking: Impulsive aggression and criminal responsibility. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 26, 723-734. doi: 10.1002/bsl.847

Tramer, M. R., Carroll, D., Campbell, F. A., Reynolds, D. J. M., Moore, R. A., & McQuay, H. J. (2001). Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: Quantitative systematic review. British Medical Journal, 323(7303), 16–21.

Urbaniok, F., Laubacher, A., Hardegger, J., Endrass, J., & Moskvitin, K. (2012). Neurobiological determinism: Human freedom of choice and criminal responsibility. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56 (2), 174-190. doi: 10.1177/0306624X10395474

Verdoux, H., Gindre, C., Sorbara, F., Tournier, M., & Swendsen, J. D. (2003). Effects of cannabis and psychosis vulnerability in daily life: An experience sampling test study. Psychological Medicine, 33, 23–32.

Wilson, J. M., Kalasinsky, K. S., & Levey, A. I. (1996). Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nature Medicine, 2, 699–703.

To view this article on LinkedIn, click here.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.